By Pete Violette (VFA#1793)

Think of my surprise, as I was reading Peter Moogk’s book “Building a House in New France” and on page 76 I see the name of one of my ancestors mentioned. In chapter four, Peter was discussing how, after signing a notarized contract to build a house – that typically no notarized contracts existed for craftsmen such as a mason or a roofer, yet he knows they were needed in order to complete the house. Peter goes on to explain that there could have been a verbal agreement or, more likely there was a “sous seing prive” which translates as “private agreement”, typically drawn up by either the contractor or home owner. Think of it much like today, when you hire a contractor to build something such as a house, typically the contractor hires what is known as sub-contractors for all the different trades (craftsmen) needed to build the house i.e. foundation workers, framers, plumbers, electricians, etc.. Peter goes to explain that these private agreements were often “brief and to the point”. A difference that we might not be familiar with is that back in the 1700s, in New France, when building a home it was typical for the client to “finish” the home. In other words, the builder would build the basic structure, but the home owner might decide, in order to save money, he would nail down his own floor boards, or as in this case, hire their own roofer to put the roof on the home.

Figure 1. Extract of John Bastide 1745 Map of Louisbourg: Courtesy clements.umich.edu

The example Peter gives for a “sous seing prive” is none other than our very own ancestor Charles Violet, and the example in Peter Moogk’s book “Building a House in New France” reads:

“I, that is me Charles Viollet [Violet], bind myself to roof the new house of Madame Poinsu with shingles [bardeau]and to supply all the shingles and nails required for the sum of 150 livres, that the said lady will pay me on St. Michael’s Day next.” (Used with permission from Peter Moogk)

Peter explains in his book that often a feast day, such as was mentioned in Charles’s contract, would be chosen as a completion date. The feast of St. Michael’s was 29 September, so they clearly wanted the roof completed before the cold and snow of fall set in.

I believe the reason the contract was made by “Madame Poinsu” (her maiden name was Bernadine Le Mauguet) is because she had lost her husband, Francois Poinsu, on 3 January 1753. Peter Moogk points out that typically, contracts for new houses, and especially if they were a “stone” house, were negotiated and signed in the fall. If you didn’t have a signed contract in the fall, you ran the risks that come spring time all the builders would be already committed and couldn’t accommodate you. We know from the 1767 map that George Sproule made, that the Poinsu house was a wooden structure, and the contract appears to have been set in the spring of 1752.

I did a search of Eric Krause’s work “Structural Documents Associated with Property Developments Fronting Rue Royalle and Rue D’Orleans” and in there I found a reference that indicates on 10 May 1752 Francois Poinsu had entered into an agreement with a master joiner for some work at block 14, lot F. In addition, there is another entry also dated 10 may 1752 where Francois Poinsu accounts for debts owed and indicates a number of construction supplies as having been purchased. Within that list is “a Violette Couvreur Cy 162”. We know couvreur translates as roofer, which was the occupation of Charles Violet, and I believe the “Cy” is a French accounting abbreviation used during the Middle Ages, or that is when I have seen it used, and always with the “livre tournois” which was a monetary unit used then. So he owed Charles 162 livres. It appears Francois Poinsu may have, back in May of 1752, been arranging for the work on his house. No doubt to make either needed repairs or to fix damage that occurred during the siege of 1745.

Figure 2. Extract of George Sproule 1767 Map of Louisbourg: Courtesy clements.umich.edu

This was Francois Poinsu’s second time for living at Louisbourg. He had lived there before the first siege which happened in 1745. And he came back to Louisbourg in 1749, after France had regained control of the whole island of Ile Royale (present day Cape Breton) during the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. During his first visit he was involved in a business with a Joseph Dugas and Jean Milly. They had obtained a charter to provide fresh beef for both the garrison and the civilian population of Louisbourg. During that time they established a butcher shop in the building at Block 4, Lot B. I can only suspect that when Francois Poinsu returned in 1749, it was in the hope of restarting that lucrative cattle import and butchery business.

For both Francois Poinsu and Bernadine Le Mauguet, this was a second marriage, both had been previously married and their spouse had died. Of interest to note, both times that Francois married, he was married in Louisbourg, and so he clearly had a very strong connection to Louisbourg.

Eric Krause, who once held the position of Historical Records Supervisor at the Fortress of Louisbourg, wrote many research papers and it was in his 2000-151 paper where I found that Francois Poinsu had owned Lot F in Block 14. When you compare the shape of the buildings on Lot F, Block 14 between the 1745 (Figure 1) and the 1767 (Figure 2) maps (red labeling added by author), it becomes obvious that the shape of the buildings on Lot F, Block 14 has changed. What I cannot be clear about, is which building in Lot F was the “new house of Madame Poinsu” mentioned in the agreement. If I was to guess, I would think it was the one on the corner, what do you think?

Figure3. King’s Bakery Fortress Louisbourg: Courtesy goggle maps

Yvon LeBlanc, the architect for Fortress Louisbourg, reported in an interview for Cape Breton’s Magazine, that buildings at rebuilt Louisbourg, have to be re-roofed every 6 or 7 years. He stated that this is due to the climate and the fact that shingles were not painted. I suspect this helped keep our ancestor Charles Violet continuously employed when he lived there.

Linda Hoad, in her report titled “Block 1, Boulangerie, Hangard D’Artillerie, New England Storehouse” she stated on page 5 that:

“The French found the building in poor condition, and in 1749, extensive repairs were carried out: the chimneys and roof were repaired…The roof was made of slate…”

Boulangerie translates as “bakery” and the King’s Bakery is one of the buildings reconstructed at the Fortress of Louisbourg (see Figure 3). Did our ancestor repair this roof back in 1749? There is no conclusive proof to say this, but the facts are that he was a “Master Roofer”, and he was there in Louisbourg when the repairs were made, therefore make the likelihood that he worked on this roof extremely high. What do you think?

Linda goes on in her report to state:

Figure 4. Woodcut showing Charpente timbers being cut: Courtesy Recuel de Planches

“The roof of the hangard [shed] was indicated for repairs also, and this work was completed by December of 1749…A rather elaborate shop for the armour was constructed in the hangard at the same time.” Later in her report she states “The hangard…was a masonry structure…with a slate roof.”

I believe that Charles had plenty of work, both repairing and replacing roofs. I suspect his services as a “maistre Couvreur” (master roofer), as he was referred to when he rented a house from Allain Le Gras in 1755, was in great need on both government buildings (which typically had slate roofs) and on the buildings of the many civilians who lived at Fortress Louisbourg (which typically had wooden shingles).

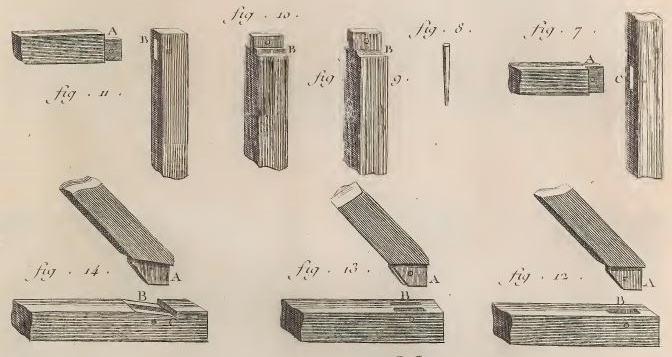

Figure 5. Charpente Joints: Courtesy Recuel de Planches

According to Eric Krause 2005 report on the use of shingles at Louisbourg, the shingles were laid over “beveled board” sheathing. The beveled board sheathing was introduced to prevent fine powered blowing snow, common in Louisbourg, from penetrating the roof. In order to keep out the weather, it was critical that the beveled board sheathing be made uniformly and installed with a tight fit. Before the use of wooden shingles became popular during the 1700s, a method of overlapping boards was used.

The wooden shingles had the common characteristics of being made with a tapered thickness, and when installed, only 1/3 of the thickest end was exposed; the other 2/3’s were covered by each successive overlapping row of shingles. Each shingle was approximately 18 pouce long (a pouce is equal to 1- 1/16 inch), by 4-5 pouce wide. The typical shingle used in Louisbourg during Charles’ time, was produced in New England and made of pine. Shingles were made by splitting wood slabs with a maul & froe. Then each shingle was dressed on a shaving horse with a drawknife, to produce the needed taper and smoothness. Each shingle required a smooth surface in order for it to seal properly once installed.

There were several different home building methods used during Charles time at Louisbourg. Colombage, which is a half-timbered construction, where the space between the wooden timbers is filled with another material, and the most prevalent method used at Louisbourg. This fill could be a mixture of masonry, stone, or brick. Or as often seen in Louisbourg, upright piquets, which are round posts, which were then filled with mortar between each piquet, see building in foreground of Figure 7 for an example.

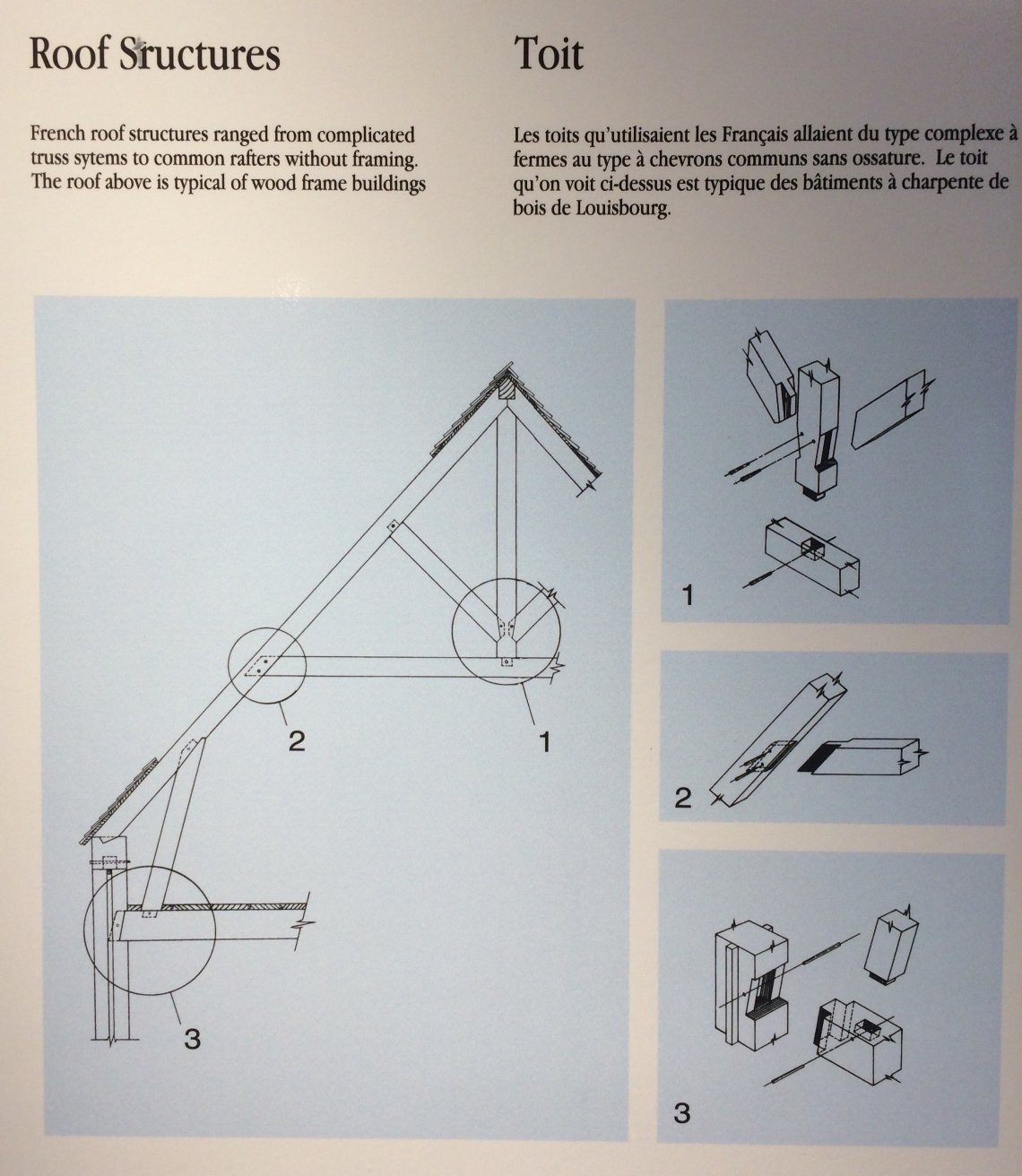

Figure 6. Photo of display panel at Louisbourg: Courtesy Author

Another method is called pieces-sur-pieces which uses a half-timbering structure similar to colombage, but one where the upright timbers are slotted to accept the tenoned ends of squared horizontal timbers which are used to fill the spaces between the upright timbers.

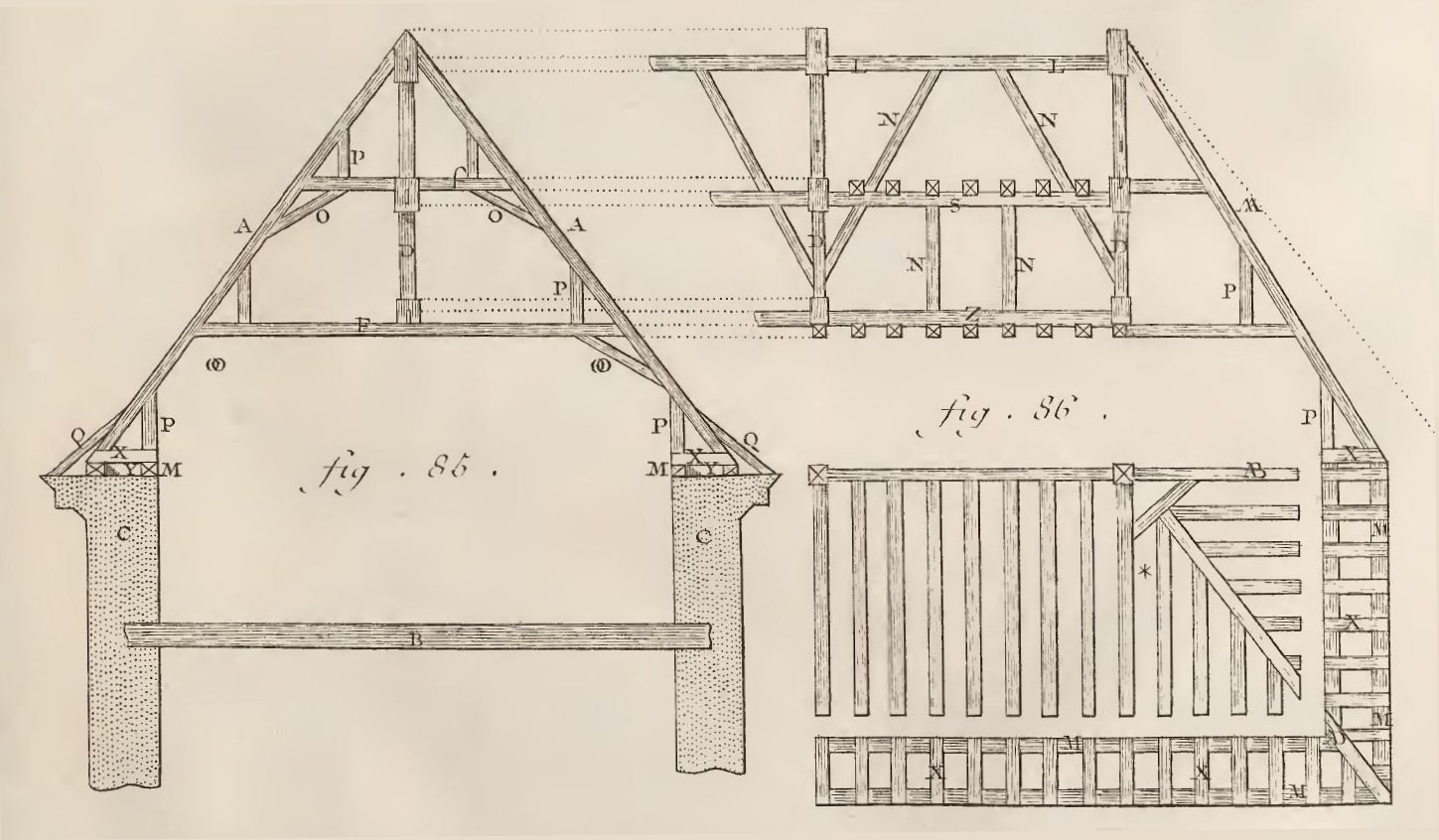

In order to build these early structures, a timber framework known as charpente was first constructed, using a method of hand cut slots (mortise) and tenoned ends on the timbers, all connected using wooden pins driven through drilled holes. This allowed the structures of early wooden buildings to be built without the use of any nails; everything was held together with interlocking joints and wooden pegs. However nails were used to hold the bardeaus (wooden shingles) on the roof (typically two nails for each shingle), the plancher (floor boards) inside the house, and the wooden “beveled board” sheathing typically used on roofs in Louisbourg to keep out the weather. During Charles’ time, each nail had to be hand made by a blacksmith, so nails were expensive and only used sparingly. During repair work, the nails were always saved and reused.

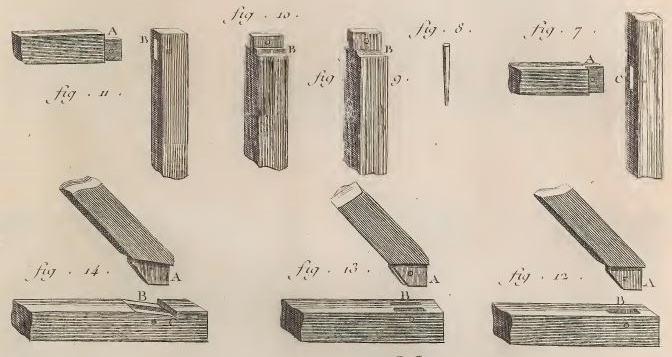

To gain an understanding of how charpente interlocking joints were made I turned to a 1762 French book written by Denis Diderot, and titled “Recueil de Planches, sur les sciences, les arts liberaux, et les arts mechaniques: avec leur explication” which translates as “Compendium of Plates, on sciences, liberal arts, and mechanical arts: with their explanation”. This old book, written in French, contained many illustrations showing how these joints were made, see Figures 4 & 5.

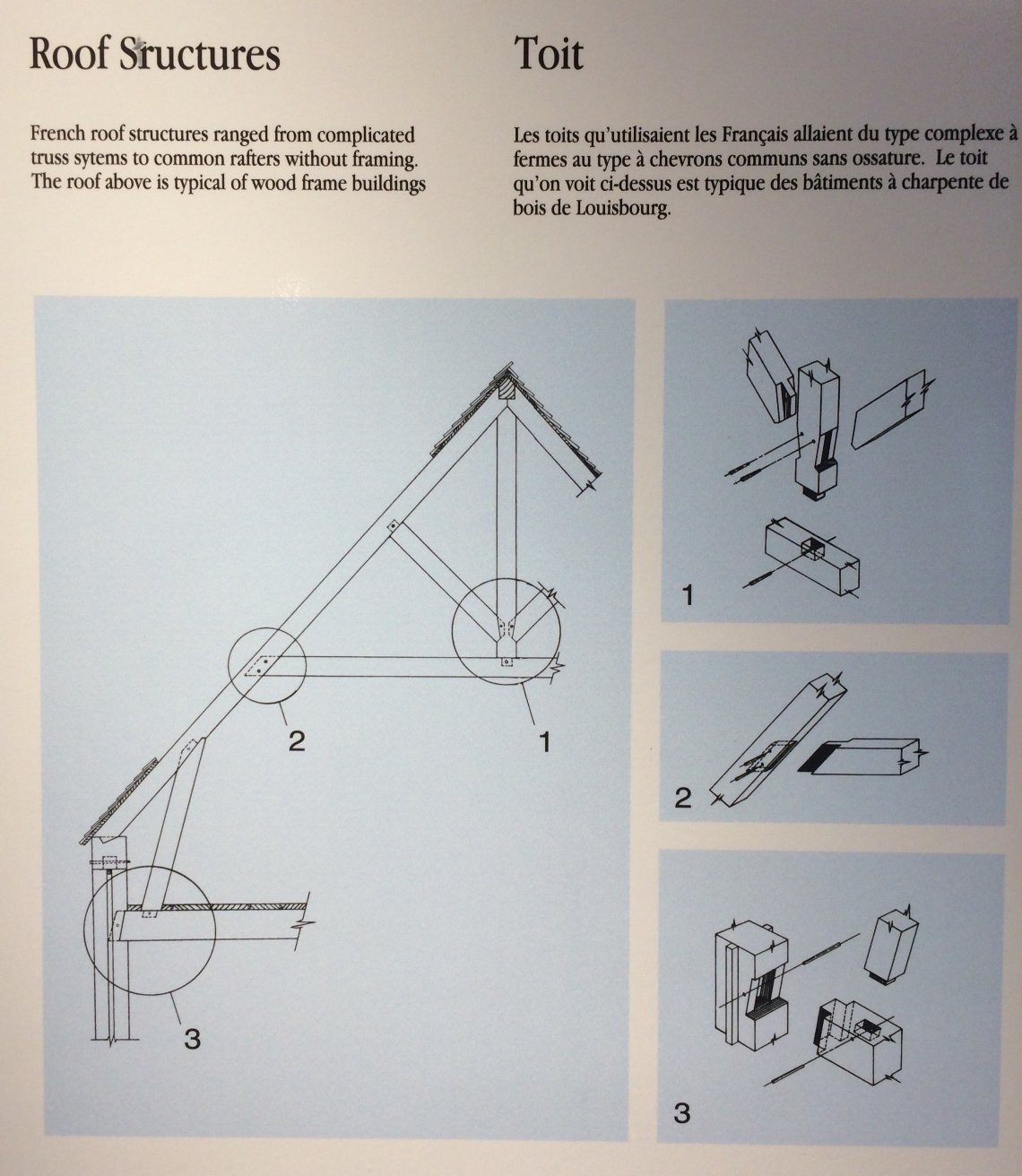

Probably, more of interest to us is how the roofs were made; see Figure 6 which is a photo of an interpretive panel at Louisbourg, which shows a typical Louisbourg roof constructed using the charpente interlocking joint method.

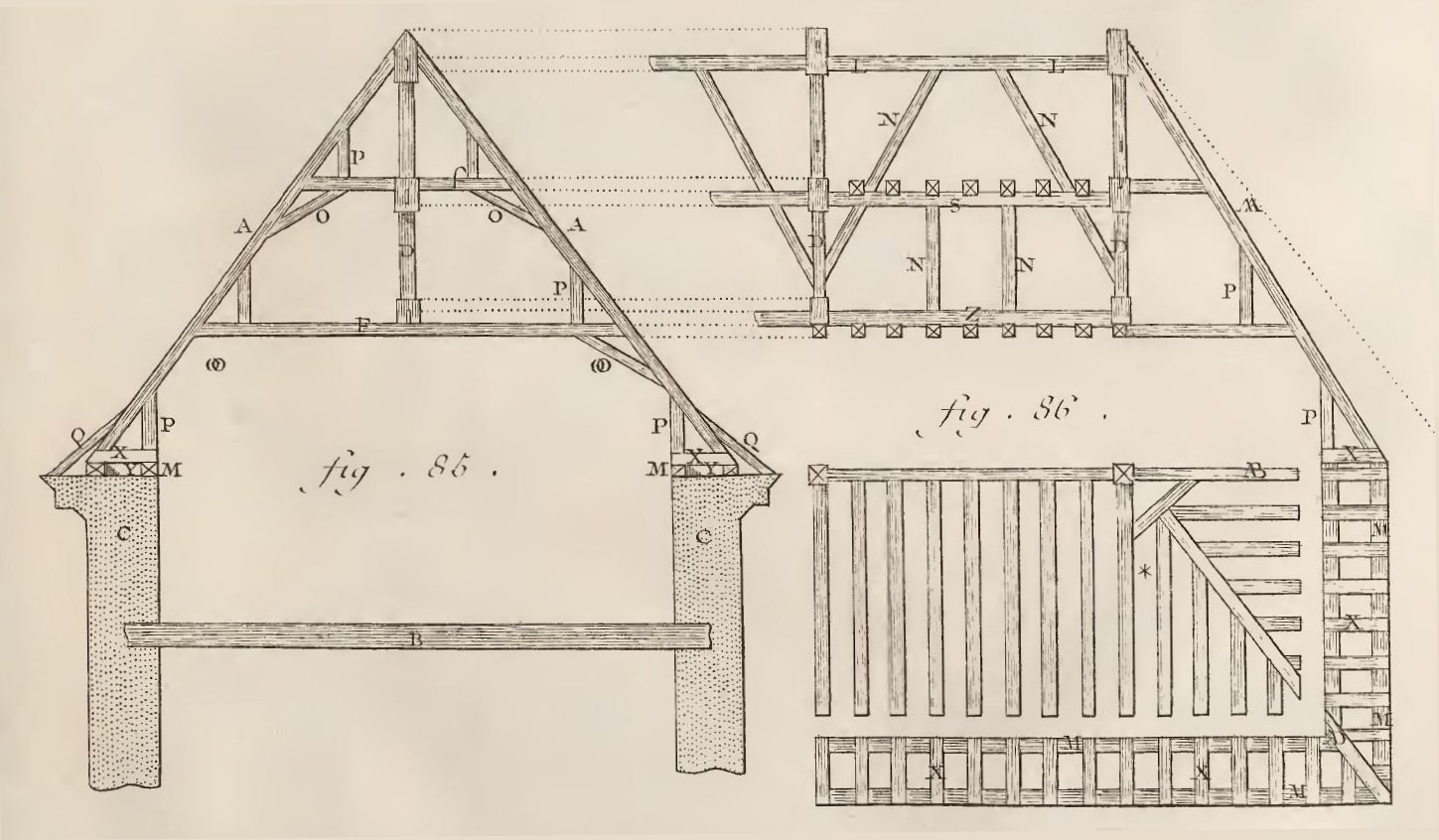

Below is an example from the book “Recueil de Planches, sur les sciences, les arts liberaux, et les arts mechaniques: avec leur explication” showing a typical French roof construction used during the 1700s, (Figure 8). Following the figure is a list, keyed to Figure 8, of the French terms of each roof component, along with the best English translation I was able to obtain using different translation sources.

A. chevrons de longs pans. (Rafters of long pieces)

Figure 8. Woodcut showing typical roof construction: Courtesy Recuel de Planches

B. poutres ou tirans. (Beams)

C. murs. (Walls)

D. poinçons. (Crown Post)

F. grand entrait. (Large Stringer)

f. petit entrait. (Small Stringer)

L. faîte. (Ridge)

M. sàblieres. (Roof Purlin/Wall Plate)

N. liens. (Links/Braces)

O. double , grands esseliers. (Large Support)

o. petits esseliers. (Small Support)

P. jambettes. (Brace)

Q. coyeàux (Coyau or Coyaux). (name for the Bell Cast Eave used on French homes)

S. soûsaîte. (Piece that makes assemblies stronger)

X. blochets. (Framing piece receiving the rafters)

Y. entretoises des sablieres. (Outside Wall Plate)

Z. liernes. (Wood piece connecting two structural members of roof)

AB. entrait de croupe. (Hip Rafter)

If you get the opportunity to visit Fortress Louisbourg, be sure to check out all the reconstructed buildings and their roofs, see Figure 7. Keep in mind that your ancestor Charles Violet helped repair and/or build many of the original roofs, during his stay between 1749, when he arrived at Louisbourg, up until 1758 when Louisbourg fell during the second British siege. Also, if you get to visit, be sure and check out the Carrerot House which has an exhibit of 18th century building techniques. It has a portion that is opened up so you can view the wooden framework of a typical 18th century roof and has on display a section of roof that archaeologists had unearthed at Louisbourg. Is it possible that Charles worked on this unearthed section of roof? If you cannot visit Louisbourg then please check out the following video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UwBqnStoAg.

Figure 7. Roofs at Fortress Louisbourg: Courtesy Author

Bibliography

Biagi, Susan, Louisbourg a Living History Colorguide, Formac Publishing Co., 1997

Diderot, Denis, Recueil de Planches, sur les sciences, les arts liberaux, et les arts mechaniques: avec leur explication, Paris, Chez Briasson, 1762, vol II

Le Blanc, Yvon, Interview published in Cape Breton’s Magazine, no. 34 (August 1983), pp. 49-60

Moogk, Peter, Building a House in New France, Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2002

Unpublished Manuscripts

Hoad, Linda, Fortress of Louisbourg Report, H D 08, Block 1, Boulangerie, Hangard D’Artillerie, New England Storehouse

Krause, Eric, Structural Documents Associated with Property Developments Fronting Rue Royalle and Rue D’Orleans Report 2000-151

Krause, Eric, Shingles, report dated 20 May2005

Myers, Susann, Restoration Architect at Fortress Louisbourg, report titled Shingles, dated 9 June 2003

Translation Sources

Larousse Chambers Dictionnaire: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003

Google Translate

Lexilogos Dictionnaire ancien francais (https://www.lexilogos.com/francais_ancien.htm)

Francois LeBlanc, Illustrated English and French Old Carpentry Terminology – Roofs (http://ip51.icomos.org/~fleblanc/documents/terminology/doc_terminology_carpentry_roofs_index.html)