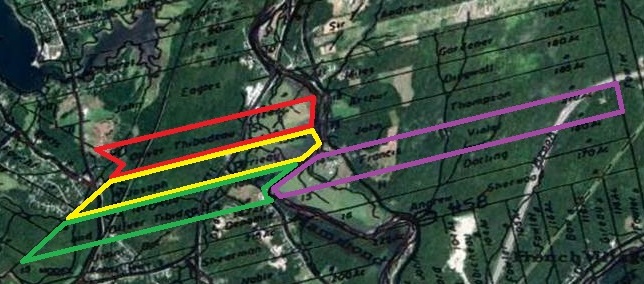

Around 1770 our ancestors François and Marie-Luce Violet settled on some in southern New Brunswick along the Hammond (Kennebeccasis) River along with several of her family and other Acadian families.The lands owned by Francois and Marie-Luce, 210 acres, are shown outlined in violet in the image above. Her older brother, Olivier Thibodeau, Sr, owned the parcel in red; Joseph Terrieau (Theriault), married to her older sister, Marie-Madeleine, owned the parcel in yellow; and Olivier and Joseph together owned the parcel in green.

Their first ownership of the land came under the old French rule but that title came into conflict with British rule in the 1780s. British Loyalist Americans and New Englanders were drawn to the area as they escaped the political climate in the newly-formed United States of America. These new residents for the most part resented the French-speaking group already there and many of the latter were displaced off their lands.

As Rita Violette Lippe reported in her Descendants of Francois Violet, pages 4 and 5:

Fortunately, two Loyalists, Edward Winslow and Ward Chipman, saw to it that some of these Acadians were made restitution by granting them the land bordering the Kennebeccasis or Hamond River, in King’s County, New Brunswick. The Land Grant in question was registered in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on the twelveth day of April 1787. The lengthy, ten- page document is entitled “Widow Sarah Hunt and Others” and describes the granting of approximately 6,888 acres divided into 42 lots. Given therein are the names of the recipients and their respective lots: Francois being granted Lot 14, a parcel of land amounting to 210 acres of the Eastern Division. The exact wording follows:.. . “unto the said John Thompson the lot Number Thirteen containing one hundred and eighty five acres, unto the said Francis Violet the lot Number Fourteen containing two hundred and ten acres, unto the said Andrew Sherwood the lot Number Sixteen containing one hundred and seventy acres” …

Noteworthy is the fact that all lots in the region were awarded by this document with the exception of one lot, Lot number 15 adjacent to Francois’ land on the south side. Why this exception? More about Lot 15 a bit later. Also noteworthy is the fact that grants were awarded such that the Acadians were dispersed among the Loyalists. In Francois’ case, his neighbors were John Thompson and Andrew Sherwood.

The document also specifies the conditions of the grant in terms of acreage to be cleared (i.e. three acres per year for each 50 granted), in terms of cattle, in terms of dwelling to be erected within three years (i.e. one good dwelling house to be at least 20 feet in length and 16 feet in breath), etc. Additionally, payment was to be made at a rate of two shillings per year per hundred acres for a period of ten years, payable at the feast of St. Michael. Annexed to the Land Grant is a plan of the subdivision of the land.

It is difficult for us who have never had to clear land to appreciate the full significance of these terms. Ponder, if you will, the toil, the labor involved in clearing 12 acres – for that was indeed Francois’ task – of virgin forest a year, and this with essentially nothing more than hand implements! In addition there was a dwelling to build, food to grow, animals to tend, a few shillings to be earned, etc… Such a task calls for a strong will, determination, physical and emotional strength, and a dedication to and a tremendous capacity for….work.

Let’s try to picture what François (and the other pioneers) had to accomplish. Twelve acres contain 522,720 square feet, or about the size of 9 football fields! That’s how much virgin forest he had to clear EVERY YEAR! And this was not sparse forest, but healthy, thick forest that had never been cut before. The Eastern White Pine tree, which is common in the area, grows to 30-50 high and covers an area 10-20 feet in diameter. If evenly spaced 20 feet apart, one acre could contain over 100 virgin pine trees so having to harvest 12 acres of forest each year might mean having to cut some 1,200 trees! And this using only hand tools such as axes. Crosscut saws made the job easier but only came into use in the 1880s – 100 years later.

To cut that many trees in a year would require an average of four trees or so per day. While doing that, François would also have to plant and tend his crops, tend his animals, build his dwelling and outbuildings, and take care of his family. I cannot imagine that kind of work!

While some of that cut timber would obviously used in building structure on his property, what would François do with the rest? No mention is made in the historic records, but this would have been no small task given that all the other pioneers were doing the same thing.

I have been on that land, shown graciously around by the current owner, Mike Steele. His family had purchased not only Lot 14 but also 15, 16, and a portion of 13 around 1960. The view from Google Maps above shows that while the lower lands have been maintained as pasture, there is still a lot of forest in the upper lands to the right in the image.

The lower, cleared, area in Lot 14 has about 90 acres, or about eight years worth of clearing.

I took the photo above from the higher area in the lower one-fourth of the Google image and looking due west; about 150 feet above the river level in the middle background. The gravel banks you can see in the left center of the photo are those at the outside of the sharp river bend in the Google image, located on the far left (west) side. That vantage point is roughly on the south line of Lot 14 and about one-third of the depth of the lot from the river.

We have to admire the amount of work those hardy pioneers had to do just to live!